.jpg?w=2000)

.jpg?w=2000)

.jpg?w=2000)

.jpg?w=2000)

At this year's MIT Gala, models walked the runway in ingenious designer garments created by 36 students, many affiliated with the MIT Morningside Academy for Design.

By Denise Brehm

Jun 20, 2025

On the first Monday of May, celebrities and fashionistas gather each year in New York City for the MET Gala, arguably the world’s most celebrated fashion event of the year. And on a Sunday evening each spring in Cambridge, MIT students now gather for their own fashion event: The MIT Gala.

.jpg?rect=449,740,3055,4516&w=2000)

This ball gown, modeled by Yihong Amy Chen, was one of ten designs presented by Chris Schmidt-Hong on the runway at this year’s MIT Gala.

Image: Michelle Xiang

MIT Gala — pronounced as two words rather than an acronym — featured runway models vamping 57 garments ranging from t-shirts to ballroom gowns to electronic wings, each created by one of 36 very ingenious student designers.

The MIT Laptop Ensemble helped set the vibe and keep the beat as the models promenaded down and back the improvised runway, surrounded by about 250 seated attendees with an overflow crowd in standing-room only. Before the 40-minute runway portion of the evening, attendees were treated to performances by MIT Hip-Hop dance teams Mocha Moves and Ridonkulous.

The Gala also included a student art show and a closing reception. Now sponsored by The Office of the Arts, the Department of Architecture, and the MIT Morningside Academy for Design (MAD), the Gala was initiated in 2023 as a launch event for the MIT student publication, Infinite Magazine.

Haydn Long (Class of ’26) has directed the runway portion of the event for two years. In 2023, she entered her own design, a dragonfly dress made for the show. Long has a double major in history and the Department of Architecture’s art and design. She plans to write her thesis on some aspect of fashion history, possibly focusing on the corset over the past 150 years.

Chris Schmidt-Hong (Class of ’27) had 10 of her designs on the runway at this year’s MIT Gala. One, an evening gown modeled by Pearl Nelson-Greene, had a princess-cut bodice that flowed directly into a 14-panel skirt made from double-brushed matte satin with beading running down the seams between panels. (Nelson-Greene is an administrative assistant in the MIT Research Lab of Electronics.) On the gown’s front is an elaborate embroidered chrysanthemum, which Schmidt-Hong fabricated on an embroidery machine in the MAD’s fabrication shop textile area. The result is a stunningly beautiful gown.

Another of her gowns (from the 2024 MIT Gala) was modeled by Nina Ojeiduma (Class of ’27). This gown, made in white satin with a chiffon overlay on the skirt, embodies 75 hours of hand beading in its bodice with another 20 to 30 hours going into making the skirt and corset, including the bodice facing, the boning channels, and adding the boning for stiffness.

Schmidt-Hong’s beadwork features swirls, flowers, dragonflies, a family crest-like emblem — even song lyrics in morse code hidden in outline. She said she added the morse code lyrics of songs she was listening to when she grew bored with beading.

“I spent a full week just sewing on this for 10 hours each day,” Schmidt-Hong said. “That was my winter break, and it was incredibly relaxing for me mentally. Then I went back for IAP [MIT’s Independent Activities Period].”

The 19-year-old from Newton, Mass., is double majoring in architecture and civil engineering. She got her first sewing machine at age 11 after her parents saw the hand-sewn ballgown she made as her Halloween costume that year.

“I mostly tend to focus on evening wear, because I really like the elegance and the sparkle, and I always have loved the drama,” she explained.

Yuru Lin (Class of ’26) modeled Schmidt-Hong’s tea-length gown featuring a dropped waist, lace-up back bodice, and tulle underskirt. The gown bodice was supported by an elegant tulle ribbon that wrapped around Lin’s neck and trailed down the back of the gown. Schmidt-Hong’s inspiration for this dress was a gown worn by actress Audrey Hepburn in “Funny Face,” a 1957 musical-comedy film.

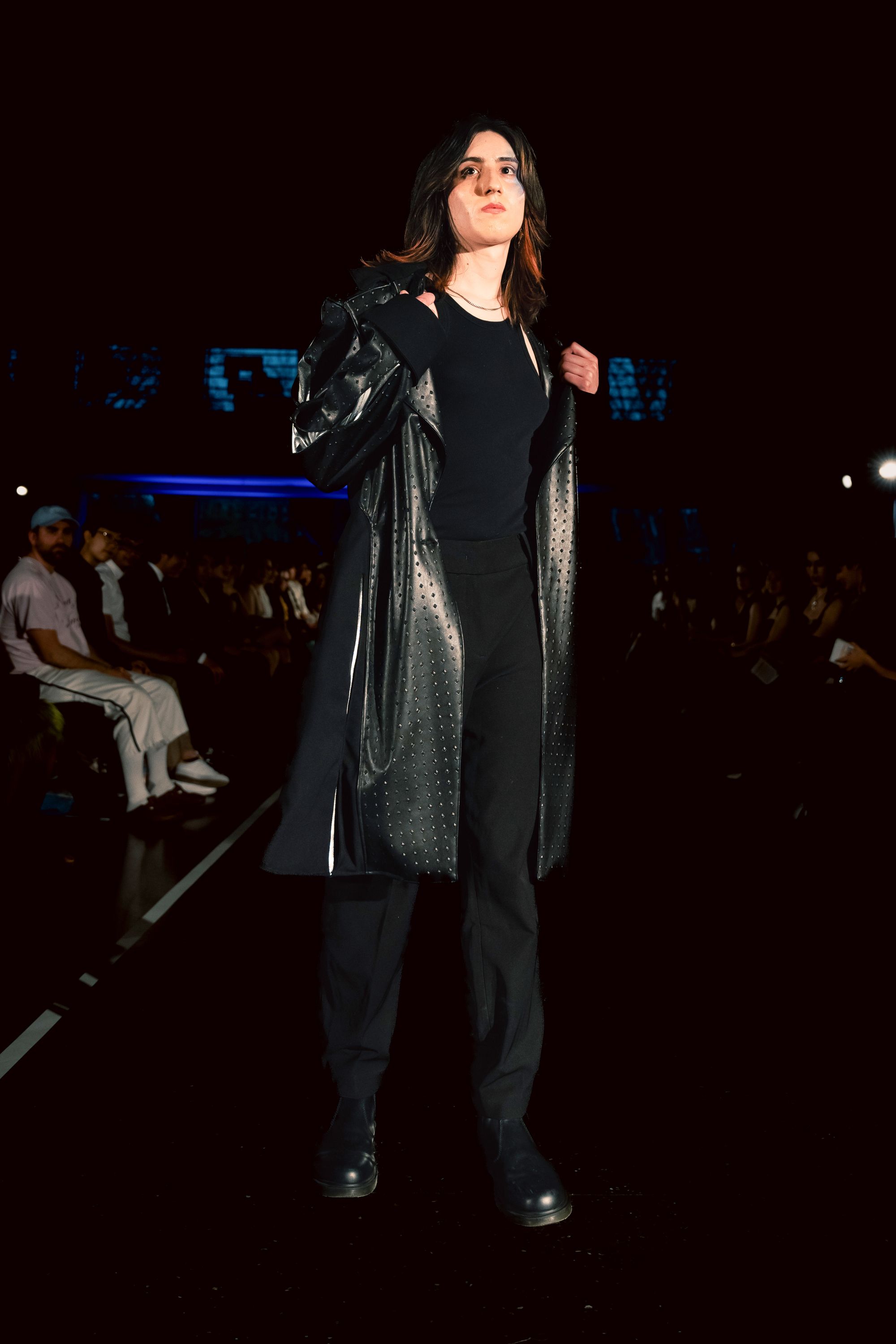

Schmidt-Hong’s most exploratory design was the full-length black jacket modeled by Chris Viets ’24 in the 2024 Gala. She made this out of studded faux leather, with five-inch-deep inserts of silver fabric tucked into openings along the seams to mimic flashes of silvery light as Viets walked.

“This one was an outlier design that took me out of my comfort zone,” she explained. “A lot of the designs of the MIT Gala are experimental, and I think that’s really cool. A lot of people do really beautiful sculptural work, whereas my garments stay in the realm of being just clothing that is pretty, as opposed to trying to push the boundaries of what clothing can be.”

An excellent example of pushing boundaries is Emily Pan’s rib skirt, modeled by Anna Chan (Class of ’26). Pan, an 18-year-old student from San Diego, spent her first year as part of the MIT MAD DesignPlus First Year Learning Community. She plans to double major in mechanical engineering (MechE) and art and design.

“I was really glad I joined DesignPlus,” Pan said. “I would be there very late in the night, just learning how to make stuff. My roommate and I would also study there sometimes. The lounge is great; there’s always snacks.”

Pan’s rib skirt closely resembles human ribs, with a sternum and spine. It slips around Chan’s waist and is worn over a simple off-white dress that Pan purchased for the occasion. (She had planned to sew a dress, but ran out of time.) The ribs are made from curved bamboo reed covered in papier-mâché tracing paper that shrank to closely hug the reeds. Slivers and small pieces of bamboo reed connect the seven rib pieces, which attach to the vertebrae in back with tiny hooks. Pan used masking tape to attach the waist support piece and other areas of the bamboo reeds, which are a natural color matching the tape.

“I did ribs, because I thought it would be cool,” Pan said. “It’s made out of the technique used for paper lantern making. I took bamboo reed, and I would bend it and then, wrap papier-mâché on it, and when the papier-mâché dried, it comes out translucent. So that’s what the sheer effect comes from. I also use some wire to kind of make it almost look like it’s floating in place. It comes out to be quite light, quite sturdy, surprising enough, and a little flexible. The front sternum piece has little wire hooks that you can just unlatch, kind of bend apart, and the model is able to put it on and off by stepping into it.”

Another first year student, Stasya Selizhuk, majoring in MechE with a design concentration, wanted to create something related to human biology for the MIT Gala.

She first considered using her embroidery skills to portray cells and perhaps a human organ, but decided that the intricate embroidered cells would not be large enough to be visible on the runway. She also wanted to learn a new skill. The lungs, she thought, would work well because they could be actual size, and could be worn as a sort-of necklace over the chest.

The result is O2, a chest plate cut from aluminum and wrapped in blue and red string evocative of the color of the inner workings of the mammalian body. The chest plate displays a stylized version of the human trachea, bronchial tubes, and bronchioles without the smaller alveoli tips.

“I wanted to create a contrast between human biology and the structure of metal,” said Selizhuk, who designed the pattern in Adobe Illustrator and cut it on a waterjet.

“I wrapped the lungs in red and blue string, which creates an interesting effect when the piece is looked at from different angles. It also makes the piece more visually appealing and plays into the dichotomy between the workings of the human body and the structured aluminum piece.”

Truman Reminicky (Class of ’28), modeled O2 worn over a dress shirt on a chain hidden beneath the collar. The piece fit over his lungs, though necessarily hangs down a few inches from his actual trachea.

Selizhuk, a 19 year old from Long Island, said the MIT MAD N52 fabrication shop is one of her favorite aspects of MIT.

“It’s really great to be able to learn how to use a lot of different tools and actually do hands-on stuff. It’s just like the MIT motto: mens et manus, mind and hand.”

Layla Stanton was codirector of fabrication for the MIT Gala along with Pria Sawhney. Both are Class of ’27. The two held a series of workshops in December to increase student awareness of the options available to them in the MIT makerspaces — particularly the MIT MAD fabrication shop — provide them with new skills, and encourage them to design for the Gala. The series included beginner’s sewing machine training, Rhino 3D and laser cutting workshop, and a general DIY course called Ruin Your Wardrobe. During the spring term, the two offered open hours for help in the shop, as well.

Stanton, who has a double major in MechE and art and design, taught herself to crochet, knit and sew during the pandemic, often doing so while “attending” high school classes remotely in the Bronx.

For the 2024 Gala, she crafted an aluminum corset consisting of 11 curved, lattice-like laser cut pieces held together by about 150 rivets. She designed the piece using software provided by Nervous System, a design firm in the Catskills that gave an MIT workshop through MIT MAD, without which Stanton may not have been able to complete her vision.

“I got the inspiration for the aluminum corset from this workshop put on by Nervous System — a design studio founded by these two great MIT alumni who create beautiful sculptures, fabrics, jewelry, and puzzles inspired by cellular biology and mathematical design,” Stanton explained.

“Basically, the software that they introduced us to, that they had created, allowed me to import my 3D model of the body that my corset then took on, and then transform it into a set of panels that, when riveted together, sort of self-assembled into the final form.”

The final form of the corset, which is incredibly graceful and elegant, was captivatingly worn over a strapless, sleeveless black dress by Aarushi Mehrotra (Class of ’26). Stanton left two panels at the back of the corset unriveted, allowing her to take advantage of the natural spring-back of the aluminum to pull those panels far enough apart to create an opening for the corset to be placed on Mehrotra’s torso.

“Securing the corset is a two-person job,” Stanton said. “One holds it in place, while the other secures it with heavy-duty yarn laced through the holes in the back panel.”

This year, Stanton again created a garment whose fabric and design seemed at odds, but instead worked seamlessly together. She sewed a full-length, strapless gown made of denim. The dress’s nine panels — varying in width from one to six inches — form flowing curves with vertical lapped seams reminiscent of long strands of jewelry. The open-cut back laces up for a delicate finish to what must be one of the more glamourous gowns ever cut from denim. Stanton’s denim couture was modeled by Mehrotra.

The largest piece in the runway show was also the only design to incorporate electronics.

The battery-operated Blade Bird — named after the song by Oklou — comprises a set of aluminum-rod wings whose motion is controlled by a device carried in a small metallic-colored purse and operated by a tiny stepper motor. The wings, motor and power source are attached to the back of the runway model with backpack straps. The effect has a spare, futuristic inclination.

Designed by Robin Liu ’25 (computer science and engineering) with a cybersigilism aesthetic, the up-and-down movement of the wings is activated when the model swivels the purse.

“Inspired by the show Neon Genesis Evangelion and the cybersigilism aesthetic and a lot of media I consume, I wanted to design something futuristic, with a mechanical cyborgish vibe,” Liu explained.

“The piece uses aluminum rods, wire, screws, a stepper motor, and 3D pointed joints and clamps to create a primitive mechanical look, while also allowing for actuated movement.”

Liu’s musical media favorites include Yeule, Aespa and FKA Twig, all of whose videos and costumes draw on cybersigilism’s use of shapes taken from nature blended with futuristic and atavistic symbols.

He first powered the bird with a tiny lithium battery, but realized there was a very slight chance — but still a chance — that the battery could catch fire while on the model’s back. So instead, he powered the wings using a small laptop that he carried, with a USB charger powering the circuit board and, in turn, the motor.

The wings were originally 10-feet in diameter, cut down to 8 feet to make walking the runway possible for Miho Koda ’25, Liu’s friend who modeled Blade Bird. The size of Liu’s entry determined its place on the runway; Koda was the last to walk, because it was logistically easier.

“Major props to her for being able to maneuver around with those big pieces,” Liu says. “I was kind of worried that she might poke someone’s eye out.” He said his initial design had little blades on the rods. But he realized that would be much too dangerous for the runway.

Blade Bird weighs about five pounds. Liu chose aluminum specifically because it’s lightweight, but also because he likes the skeletal look of the narrow rods. “Kind of like a bird skeleton is really light and really thin, that was the design choice behind that,” he said.

Liu, a 22 year old from the San Francisco Bay area, used the Metropolis makerspace run by MAD Making when he was first learning design. He built Blade Bird in the Engineering Design Studio in Building 38, and credits lab instructor Anthony Pennes for providing help crucial to completing the device.

“This was a very collaborative project, because my close friends worked in the lab, and I’d be like, ‘Hey, my wings aren’t moving, because I don’t understand physics.’ And the guys would be like, ‘Oh, you need this to restrain this joint,’” Liu said with a laugh.

“I’m happy that my final big project was representative of what I like about MIT as a whole, which is: a lot of people with different expertise coming together to help each other out.”

“I’m happy that my final big project was representative of what I like about MIT as a whole, which is: a lot of people with different expertise coming together to help each other out,” says Robin Liu.

Video courtesy of Robin Liu

May 9, 2024

Jun 8, 2023

Aug 22, 2024