Computer science students design AI chatbots to help young users become more social and socially confident

By Denise Brehm

Feb 17, 2026

Young adults growing up in the attention economy — preparing for adult life with social media and chatbots competing for their attention — can easily fall into unhealthy relationships with digital platforms. But what if chatbots weren’t mere distractions from real life? Could they be designed humanely, as moral partners whose digital goal is to be a social guide rather than an addictive escape?

At MIT, a friendship between two professors — one an anthropologist, the other a computer scientist — led to creation of an undergraduate class that set out to find the answer to those questions. Combining the two seemingly disparate disciplines, the class encourages students to design AI chatbots in humane ways that help users improve themselves.

The class, Humane User Experience Design 21A / C36 (Humane UXD), is an upper-level computer science class cross-listed with anthropology. This unique cross-listing allows computer science majors to fulfill a humanities requirement while also pursuing their career objectives. The two professors use methods from linguistic anthropology to teach students how to integrate the interactional and interpersonal needs of humans into programming.

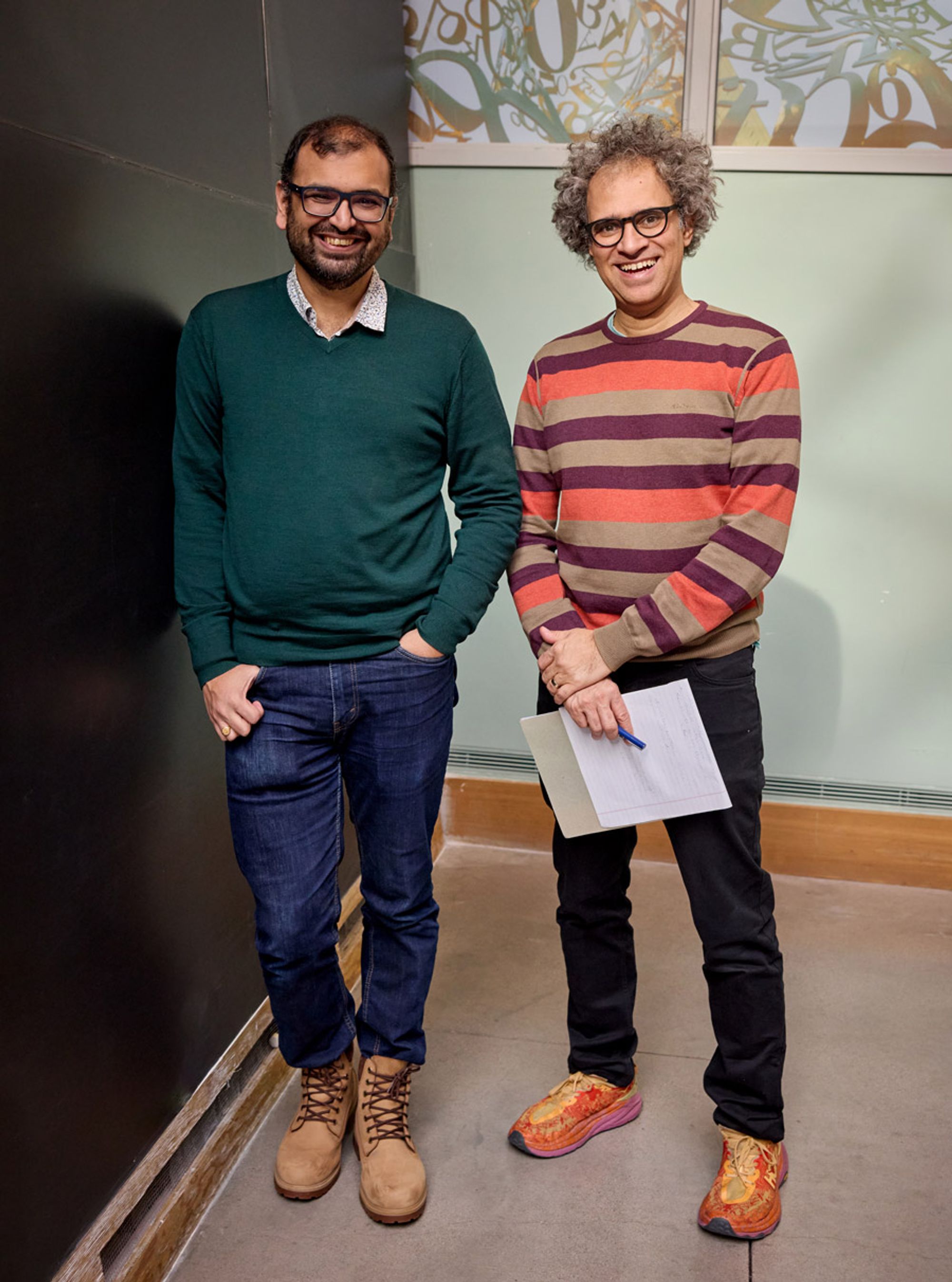

Professor Arvind Satyanarayan, a computer scientist whose research develops tools for interactive data visualization and user interfaces, and Professor Graham Jones, an anthropologist whose research focuses on communication, created Humane UXD last summer with a grant from the MIT Morningside Academy for Design (MAD). The MIT MAD Design Curriculum Program provides funding for faculty to develop new classes or enhance existing classes using innovative pedagogical approaches that transcend departmental boundaries.

The Design Curriculum Program is currently accepting applications for the 2026-27 academic year; the deadline is Friday, March 20.

Jones and Satyanarayan met several years ago when they co-advised a doctoral student’s research on data visualization for visually impaired people. They’ve since become close friends who can pretty much finish one another’s sentences.

“There’s a way in which you don’t really fully externalize what you know or how you think until you’re teaching,” Jones says. “So, it’s been really fun for me to see Arvind unfurl his expertise as a teacher in a way that lets me see how the pieces fit together — and discover underlying commonalities between our disciplines and our ways of thinking.”

Satyanarayan continues that thought: “One of the things I really enjoyed is the reciprocal version of what Graham said, which is that my field — human-computer interaction — inherited a lot of methods from anthropology, such as interviews and user studies and observation studies. And over the decades, those methods have gotten more and more watered down. As a result, a lot of things have been lost.

“For instance, it was very exciting for me to see how an anthropologist teaches students to interview people. It’s completely different than how I would do it. With my way, we lose the rapport and connection you need to build with your interview participant. Instead, we just extract data from them.”

For Jones’s part, teaching with a computer scientist holds another kind of allure: design. He says that human speech and interaction are organized into underlying genres with stable sets of rules that differentiate an interview at a cocktail party from a conversation at a funeral.

“ChatGPT and other large language models are trained on naturally occurring human communication, so they have all those genres inside them in a latent state, waiting to be activated.” he says.

“As a social scientist, I teach methods for analyzing human conversation, and give students very powerful tools to do that. But it ends up usually being an exercise in pure research, whereas this is a design class where students are building real-world systems.”

The curriculum appears to be on target for preparing students for jobs after graduation. One student sought permission to miss class for a week because he had a trial internship at a chatbot startup; when he returned, he said his work at the startup was just like what he was learning in class. He got the job.

The sampling of group projects below, built with Google’s Gemini, demonstrates some of what’s possible when, as Jones says, “there’s a really deep intertwining of the technology piece with the humanities piece.” The students’ design work shows that entirely new ways of programing can be conceptualized when the humane is made a priority.

The bots demonstrate clearly that an interdisciplinary class can be designed in such a way that everyone benefits: students learn more and differently; they can fulfill a non-major course requirement by taking a class that is directly beneficial to their careers; and long-term faculty partnerships can be forged or strengthened.

One project promises to be particularly useful for graduating seniors. Pond is designed to help young college graduates adapt to the challenges of independent adult life. Team Pond configured the chatbot not to simply parrot the user nor to sycophantically praise wrong answers. Instead, Pond provides advice to help with adulting.

“Pond is built to be your companion from college life into post-college life, to help you in your transition from being a small fish in a small pond to being a small fish in a very big pond,” says sophomore Mary Feliz.

“College is very much a high-proximity and high-context environment, in the sense that everybody around you is going through the same thing, and it’s easy to build relationships or find opportunities, because there are structured pathways that you have access to,” explains graduate student Emaan Khan. “Post-grad life, is low-context. You’re not always surrounded by your peers or your professors. It’s no-proximity also in the sense that you don’t have opportunities at your doorstep. Pond is a tool to help empower you to access certain opportunities or learn how to navigate.”

Pond’s developers are graduate student Claire Camacho, Harvard graduate student Charlotte Cheah, Feliz and Khan. They trained Pond to offer expertise in three areas: social life, professional life, and adult skills.

The students demonstrated Pond’s social communication by asking how to start conversations in a hobby group. Next, they exhibited Pond’s adulting communication by typing in a question.

“My landlord has asked me personal questions that make me uncomfortable. What should I do?”

Appearing in Pond’s textbox was this response: “Politely set boundaries. You are not obligated to answer personal questions. You can gently redirect the conversation back to property-related topics. Know your rights: Familiarize yourself with tenant rights in your city or state regarding privacy and landlord conduct.”

When asked how to do that, Pond offered specific instructions: “You can try saying phrases like:

‘I prefer to keep our conversations focused on the property’ and ‘Let’s stick to topics related to the apartment, please.’ Always redirect the conversation back to the apartment or a legitimate maintenance issue. Keep your tone polite but firm. Document any conversations if needed.”

Pond also offered a role-playing scenario to help the user learn what polite but firm language might be in that situation.

“The ethos of the practice mode is that you are actively building a skill, so that after using Pond for some time, you feel confident that you can swim on your own,” Khan says. The chatbot uses a point system that allows users to graduate from a topic, and a treasure chest to store prizes, elements added to boost the bot’s appeal.

Another of the projects, News Nest, provides a sophisticated means of helping young people engage with credible news sources in a way that makes it fun. The name is derived from the program’s 10 appealing and colorful birds, each of which focuses on a particular area of news. If you want the headlines, you ask Polly the Parrot, the main news carrier; if you’re interested in science, Gaia the Goose guides you. The flock also includes Flynn the Falcon, sports reporter; Credo the Crow, for crime and legal news; Edwin the Eagle, a business and economics news guide; Pizzazz the Peacock for pop and entertainment stories; and Pixel the Pigeon, a technology news specialist.

News Nest’s development team is seniors Tiana Jiang and Krystal Montgomery, and junior Natalie Tan. They intentionally built News Nest to prevent doomscrolling, provide media transparency (sources and political leanings are always shown), and created a clever, healthy buffer from emotional manipulation and engagement traps by employing birds rather than human characters.

A third team, M^3, decided to experiment with making AI humane by keeping it fun. Senior Rodis Aguilar, junior David De La Torre and sophomore Deeraj Pothapragada developed M^3, a social deduction multi-agent murder mystery that incorporates four chatbots as different personalities: Gemini, OpenAI’s ChatGPT, xAI’s Grok and Anthropic’s Claude. The user is the fifth player. Like a regular murder mystery, there are locations, weapons and lies. The user has to guess who committed the murder. It’s very similar to a board or online game played with real players, only these are enhanced AI opponents you can’t see, who may or may not tell the truth in response to questions. Users can’t get too involved with one chatbot, because they’re playing all four. Also, as in a real life murder mystery game, the user is sometimes guilty.

Jul 21, 2025

Sep 6, 2024

Nov 20, 2025